2002 – Converge: Where art and Science meet: The Adelaide Biennial, The Art Gallery of South Australia, 2002 -The 13th Sydney Biennale of Sydney, The world (May Be) Fantastic, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia.

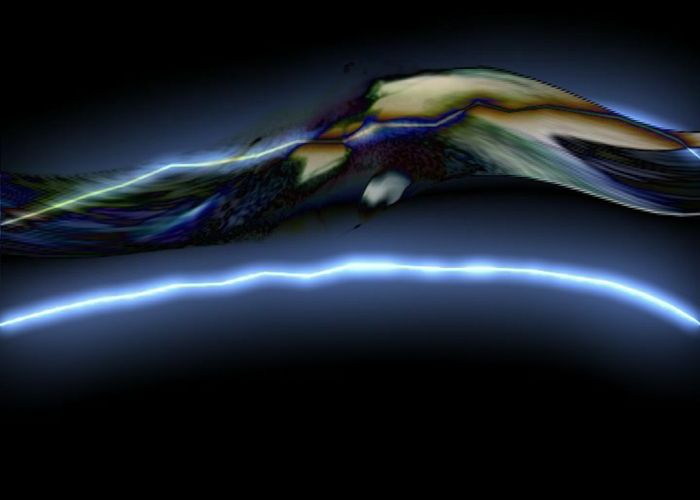

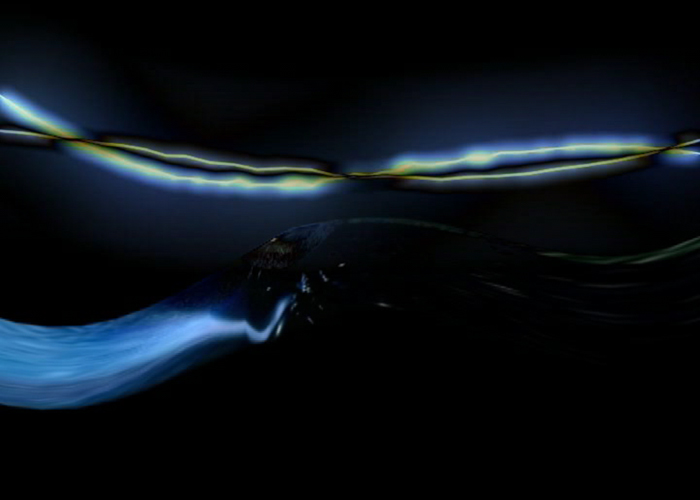

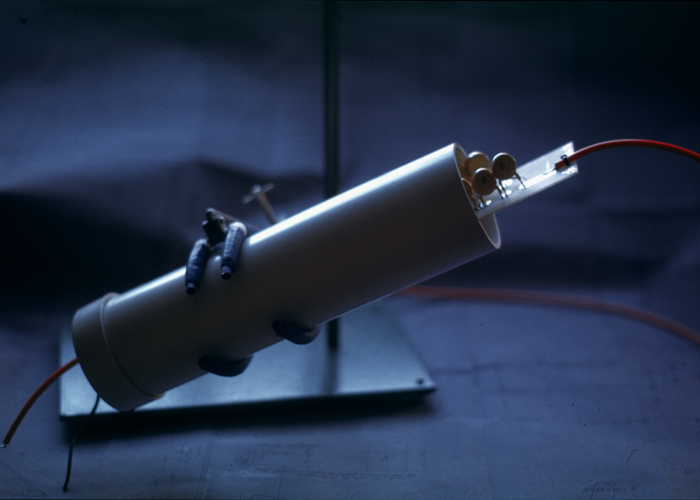

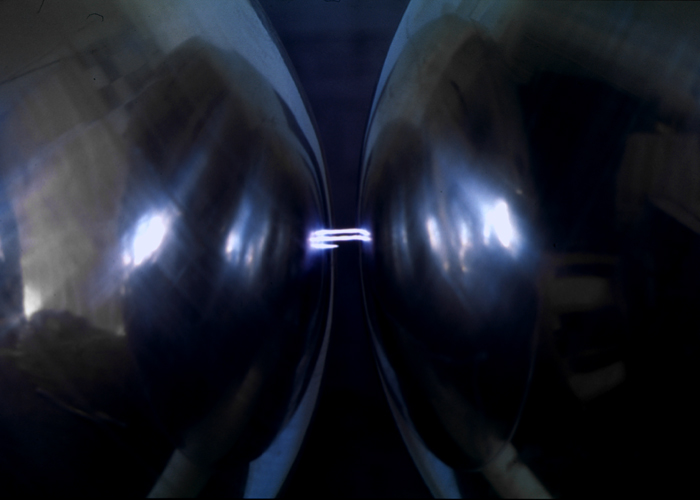

The Plasma Wave Instrument explores the in-between space of matter both as a real-world phenomenon and as an imaginary rendering via a computer-generated sequence. At the centre of this work is a photovoltaic high-voltage generator that transforms sunlight into plasma. Here, the air in its fourth phase travels faster than the speed of sound, literally burning the air.

The mechanism that facilitates this is based on modified television technology; instead of presenting coherent television pictures on a phosphor screen, the acceleration produces light and radio waves orchestrated by the photo-voltaic exchange in the silicon. This work was developed with consultation from Rob Largent from the University of New South Wales Center for Photovoltaic Devices and Systems and supported by the Australia Council for the Arts.

Air-time: The Logic of the Supplement. Ann Finegan

Call it a phenomenon in search of an imaginary. Viewed as a system that mediates the multiple transformations of energetic states, this is a work bound up in matter-as-phenomenon, or material aggregate. Yet, it is a concrete poem on the imaginary plane, a machine for manufacturing thoughts. The reply to the questions of ‘What is it?’ or ‘How does it work?’, ‘What is it for?’ etc., return to a thought or a series of thoughts stimulating the mind. On the one hand, there is the raw phenomenon, stripped back to the functionality of a grunge or minimalist technology. Then there are the video screens fictionalising the processes at work. The material plane of the phenomenon is thus exchanged for the expressive. This is not illustration in the sense of drawing or reproducing what something looks like to the eye, as in representing the thing, but a crossing over of the manifestation of a phenomenon (the entire complex of the plasma burning/ air time event) into the plane of the imagination. You have to figure out the assemblage and what it is for, then trace lines of linkage from material aggregate to the plane of expression. The machinic complex becomes an image (rather than the image reproducing the machine’s appearance) and takes off elsewhere into fictive apprehensions of a work which, technically, can’t be seen ‘on its inside’, as a process, as functionality. Hinterding is adding the visual supplement of what can only be made up.

The supplement supplements. According to an early Derridian ‘law’, the supplement is always supplementary to any original and never its completion. The work of the supplement paradoxically ‘adds nothing’ to the work as a phenomenon, and yet is the addition through which the work disseminates. Science is full of supplements – diagrams, formulas, charts and ideas – without which the work is said to be incomplete, and yet the supplement does not literally complete it in the same material plane but rather supplements, extends and explains. It does what the work itself cannot do: translate and inform upon itself.

The phenomenon, then, can’t reflect on itself but can only call upon the supplement to ‘duplicate’ in translation, in other words, not to duplicate ‘per se’ but to translate to another plane, that of expression.

Derrida theorizes this somewhat conflicting and contradictory relation. The supplement threatens to take over, usurping the first place of the original. The image supplants the thing, becoming more important. Or does it? Is it really a question of priorities or origins but rather the undecidability of an incommensurable relation between two parts of a work, which simultaneously exists in two planes?

Can’t a work be said to begin in the middle, in a process of reflection that is as much bound up with material phenomenon, however partially realized, and the play of the idea which is realized by inspiration? For an artist coming upon phenomena, the conceptual process goes both ways, exploring both things and images. As such the two aspects of the work, material phenomenon and image plane, can be read from either direction. Beginning with the image, the assemblage comes into being to manifest the idea as a supplementary material counterpart; conversely, reading from material assemblage to image, the image becomes supplementary to the machine by explaining it. There’s a

complementary supplementarity in which both aspects supplement the other. This undecidability links the incommensurable parts and makes them indispensable to each other. It becomes nonsensical to ask which comes first, thing or image?

Rather, to put two and two together, you have to mentally image one aspect in the other; the image wraps itself inside the machine in order to mimic, however ‘wrongly’, for want of a true image, the interior electronic flows; equally, the machine could be said to literally wrap or engulf the image which expresses the content of its processes. Both wrap around each other, confounding the inside/outside relation, whilst remaining absolutely incommensurable.

Thus, the image is both inside and outside the ‘work-as-phenomenon’: an exterior depiction of what’s going on inside. The inside is the outside, and vice versa, but projected as disjunctive surfaces which never match. You can’t turn a machine transforming electromagnetic streams inside out like a glove. Instead, there will only be a differential of surfaces and planes.

In a sense, it doesn’t matter whether one understands exactly what is being produced by the technological apparatus (apparently matter in its fourth state). The work unfolds through the logic of the supplement in which the imaginary informs the material work, at the same time as the material work produces the imaginary, without any sense of equivalence between the processes. There is translation, from phenomenon to image and from image to phenomenon, and the actual states of energetic transfer and transformation going on inside the ‘machine’. Even though Hinterding can accurately describe the actual energy transfers and flows inside the “plasma wave instrument”, this is never reproduced diagrammatically as image. Therefore, there’s no technical correlation between “how it works” and the dynamics of the images on the screens, which remain purely imaginary. The profound disjunction between image and machine is respected, even though both the material and imagistic planes are inextricably intertwined, one inside the other.

On a technical note, the machine can be described as aberrant TV. Hinterding has taken television’s electron-gun or ray technology and unhooked this process from image transmission. What is left is the raw process of transmission itself, matter in its fourth state as plasma detectably burning the air. The reference to “air-time”, one of the working titles was thus to TV’s own phenomenon and less about the content of being “on air”. Air-time is the guts of deviated TV: its stepped up voltage is no longer pumping out high speed electrons to contact a picture screen but generating, instead a pure plasma stream. Paradoxically, Hinterding is imaging that part of the process of TV, which is without image.